Artist speaks on combating environmental problems with art

Nina Elder hopes that her drawings will raise concern for environmental problems like species loss and deforestation.

March 23, 2020

Nina Elder, an artist, researcher and lecturer, visited campus on March 3 for a public lecture as part of the Department of Art, Media and Design’s CoLab Series of Visiting Artists.

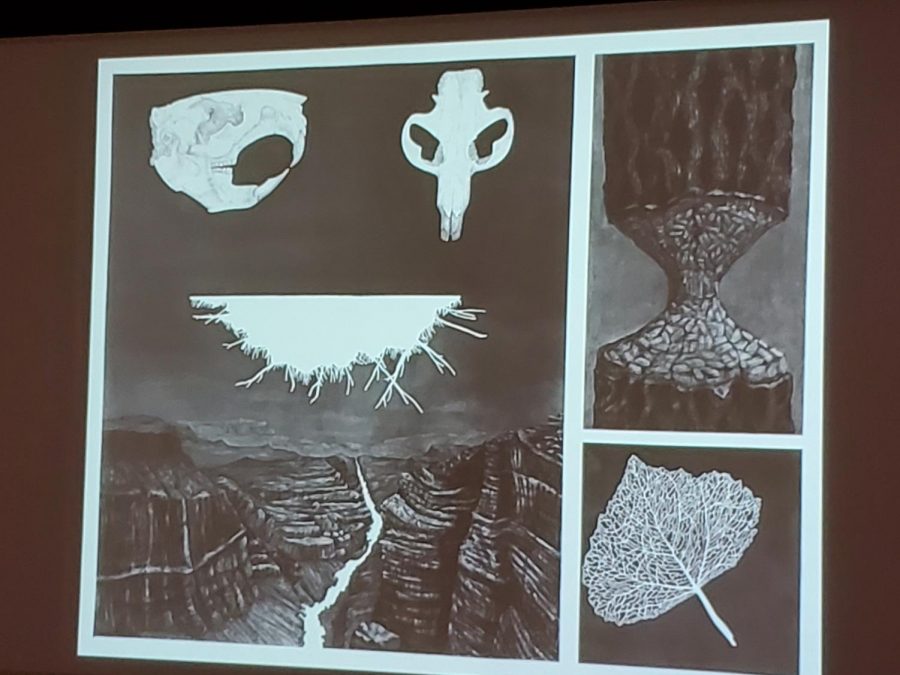

“I make work about disruptions. I’m obsessed with holes in the ground and piles of rocks,” said Elder, whose primary medium is drawing.

The focus of her work is the relationship between the natural environment and human activity. She noted that so many of the objects we use daily, such as medicine, cleaning products and money, depend on extracting natural resources.

Elder discussed how her time in Alaska influenced her work as an artist. During her first trip to Alaska, she visited the small town of McCarthy, which is located within the Wrangell–St. Elias Wilderness.

The area Elder visited was near Kennecott Mines, which previously harvested tremendous quantities of copper.

“When I first came to McCarthy, I wanted to hate the mine. I’m an environmentalist! But the more I learned, the more I [became] purely fascinated by and attracted to the complexity of the place,” said Elder. “The scale of human ambition was astounding. The level of innovation was remarkable.”

However, Elder makes a distinction between Kennecott Mines and contemporary mining sites. “Unlike [Kennecott Mines], these sites are renowned for their voracious consumption of space and their unparalleled negative environmental impact,” she said.

Elder made it her project to make large-scale drawings of such modern mines to bring attention to the enormity of their effect on the environment. Each drawing takes her about a month to complete and is a “contemplative” process for her. “I feel like I am memorializing wilderness lost and illuminating the triumph of consumerism,” she said.

Another of her projects is a series of drawings on meteorites. Meteorites are revered as sacred objects by indigenous people around the world but are often collected by museums for scientific study. She depicts the meteorite as a blank white space to signify the void their absence leaves on indigenous people.

Within this project is a drawing of the Ontonagon Boulder, a 3,708 pound copper boulder originally from Michigan. The boulder was removed from its location in 1843 and is now possessed by the Smithsonian Institution.

Native American groups unsuccessfully petitioned the government to return the boulder in 1991. “How can a museum hold a sacred stone hostage? How does a community memorialize what is gone?” said Elder. She said she hopes that her drawings will honor these sacred objects and bring attention to the situation.

Elder also creates drawings about deforestation and extinction. “The world is facing unprecedented challenges and so much loss,” she said.

“What can I learn from the past? What exists now that will disappear?” she said. “What is being destroyed that one day we will desperately miss?” She hopes her work will help viewers ask themselves such questions and motivate them to change the course of the future.

Despite the environmental problems we face, Elder said it is important to retain a sense of wonder at the natural world. “Even as I continue looking into the abyss, I want to retain my wonder and hope,” she said. She said she tries to balance the urgency of taking steps towards environmental stewardship and the importance to slow down and enjoy life.

Ultimately, Elder is hopeful that we can improve the state of the natural world in the future. “Spending time in this landscape made me realize that curiosity and empathy are really what is necessary to move with vitality into the future,” she said.

Learn more about Elder and her work at ninaelder.com.